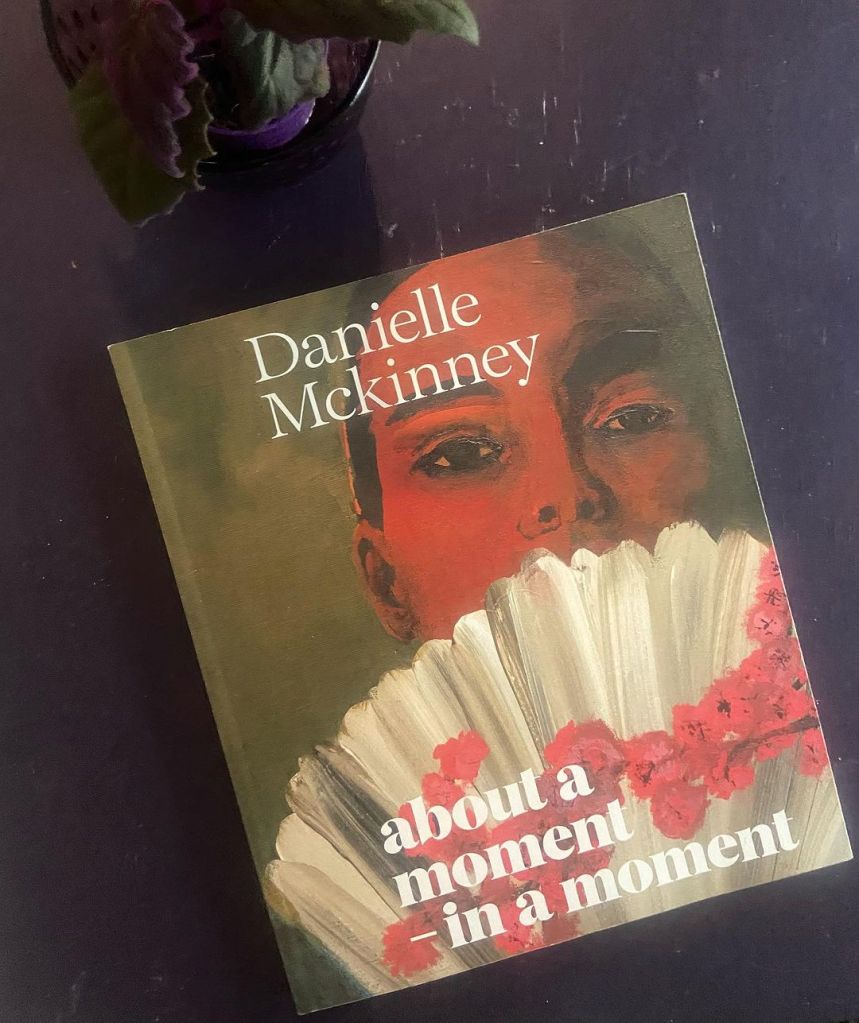

Quiet Defiance

The art of otium in Danielle Mckinney’s work

by Paola Paleari

In ancient Roman culture, the concept of otium was a multifaceted idea encompassing leisure, ease, and moments of inactivity, ranging from a simple pause to sheer indolence. It was a time dedicated to personal reflection, self-knowledge, and the pursuit of intellectual and spiritual growth. The Stoic philosopher Lucio Anneo Seneca emphasized in his 1st-century treatise De Otio (On Leisure) that otium was not synonymous with idleness but rather an active engagement with the self, a journey inward to discover one’s true purpose and achieve lasting happiness1. In this state, individuals could contemplate their existence, engage with the world thoughtfully, and cultivate a deeper understanding of themselves and their surroundings.

I encountered this concept for the first time in my high school years, where it was introduced to my unripe mind by an old Latin professor whose unruly hair and thick beard ironically matched those of the ancient Roman philosopher. It must nonetheless have landed in a fertile place, because the idea of “non-doing” as a form of personal and collective advancement has lingered in my mind ever since.

After seeing Danielle Mckinney’s work, I cannot think of anything that better embodies this ancient ideal in a contemporary context. To begin with, her paintings are sensorially soothing—an excellent start to rewire the brain for tranquility. Their dusky colour palette is rich in nuances whose expansion reaches deep rather than large, with patches of vividness that originate in one point and spread under the surface through the whole canvas. Their quiet, almost drowsy quality reminds me of the endless summer afternoons spent indoors in my childhood house in Northern Italy, with the shutters half closed to let the breeze in and keep the heat out—infinite hours lying in the dim light, listening to the spare sounds of the few venturing outside in the scorching sun.

Danielle Mckinney, Safekeeping, 2023

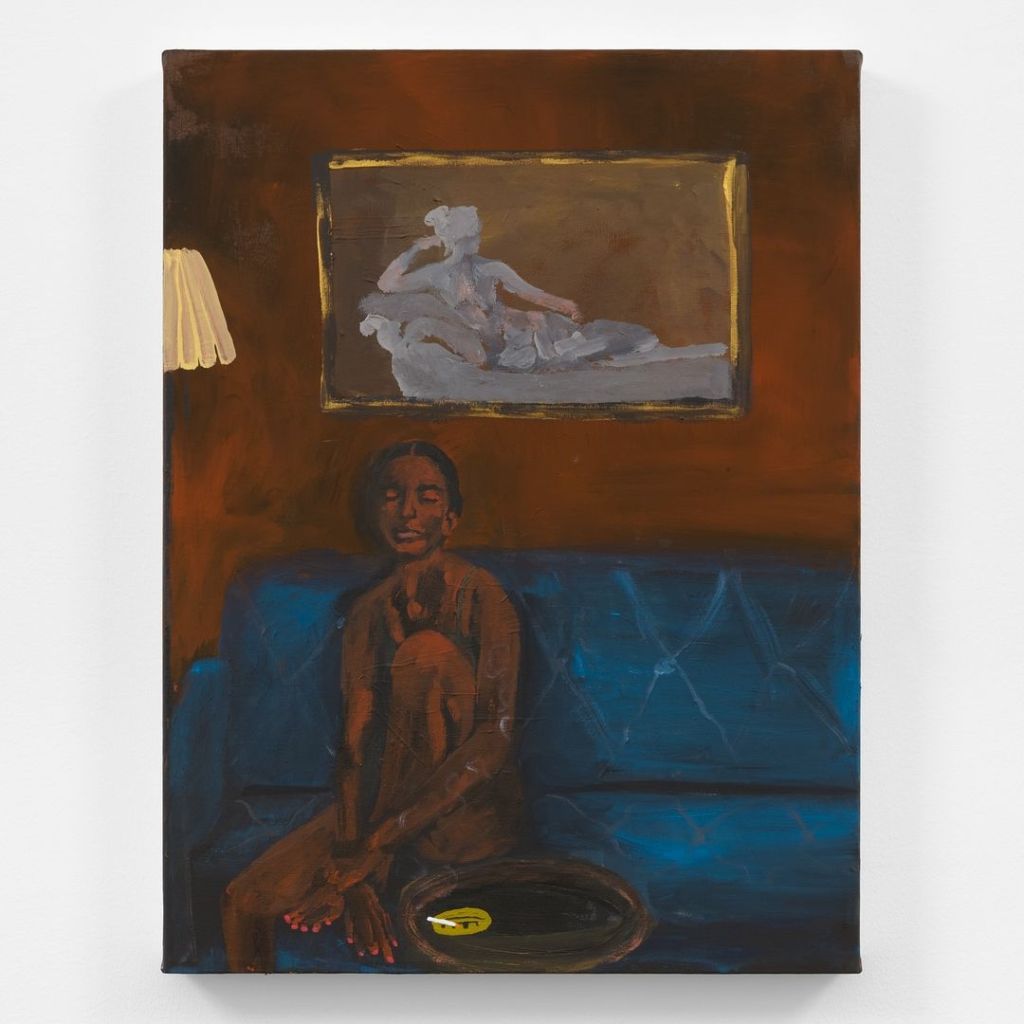

An air-conditioned environment is supposed to keep one fresh, comfortable and active despite the swelter, and my impression is that none of Mckinney’s domestic interiors has air-con. I don’t get to see so much of those rooms—no more than a blanket, the corner of a sofa, a lamp—but what I am presented with is enough to be able to feel them. They are unproductive and intimate places that host solitary Black female protagonists in moments of repose, engaged in activities such as reading, smoking, or simply thinking. These women are portrayed in a state of profound rest and contemplation—in a state of otium. Significantly, there are no screens to be found in these women’s alcoves, not even in the form of mirrors. The only devices are books, cigarettes, food or drinks—and occasionally other paintings, often of religious or art historical significance.

I find this element—the intentional exclusion of screens vs. inclusion of icons—quite meaningful for two opposite reasons.

On the one hand, it is interesting in relation to the fact that Mckinney’s painterly practice is rooted in her background in photography.2 The photographic eye is capable of a special kind of alchemy: to recognize the extraordinariness in ordinary moments and preserve them in their property before the flow of things inevitably undo them. Mckinney’s eye is undoubtedly photographic, and the power of her paintings lies in their ability to capture those moments of pause that would otherwise go unseen. Even the way the image is materially built on the canvas bears the legacy of a habit of watching the world through the viewfinder.3

On the other hand, the photographic culture has become a significant infrastructure in the online negotium of 24/7 sharing and connection, and the screen is the vehicle enabling the performative selfhood of post-capitalism.4 In stark contrast to that, the women in Mckinney’s portraits are depicted in states of being that are irresolute, nonproductive, and unapologetic: a close-to-nothingness increasingly rare in our fast-paced society where even rest and self-care have been largely commodified. The quality of painting is most evident here, as the very same poses and situations, if photographed, would appear contrived or at least staged.

While writing this text, my mind goes back to Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation. The novel, published in 2018 and set in New York City on the eve of 9/11, tells the story of a young woman who, disillusioned with the emptiness of modern life, decides to spend an entire year in a condition of drug-induced sleep. She is clearly an antihero against a backdrop “where everyone except the narrator seems beset with delusional optimism, horrifically carefree”5 and her extreme inducement of rest serves as a form of rebellion against the societal expectations of constant productivity.

I recognize a similar stubbornness in Mckinney’s protagonists and an akin anarchist resistance to the dictat of business, but not the same level of discontent and nihilism. Quite the opposite, the subject on the canvas is a female lead who is aware, awake and proud of her identity, gender and race, as well as her imperfect and age-defined appearance.

Danielle Mckinney, Stay Put, 2022

It is here—in the reclamation of her place in the universe—that the presence of a “metapainting” plays a crucial role. In Stay Put, a naked woman sits on a blue sofa with closed eyes and a lit cigarette resting in an ashtray. Above her head and slightly to the right, so it is perfectly central to the viewer, is a reproduction of the Neoclassical sculpture Paolina Borghese Bonaparte as Venus Victrix by Antonio Canova. The symmetry between the two women is almost absolute, as if they were complementary and, at the same time, opposing forces. Both bodies laze on pillowed couches and have a languid and voluptuous attitude that seems to be whispering Billie Holiday’s words: “Love me or leave me and let me be lonely”. Despite their distance in time and space, they are allies.

This interplay between past and present highlights the enduring influence of classical aesthetics while simultaneously challenging them through a contemporary lens. Mckinney’s work becomes a site of reclamation and redefinition, where the histories of art and the lived experiences of Black women intersect.

I fell pregnant with my child in the fall of 2020, when COVID was still keeping us home and divided, and the forced inactivity made many of us restless and insecure. I couldn’t know back then that both events—the pandemic and motherhood—would totally change how I look at many things, art included. Time has a totally different meaning for me now, and I am grateful to have encountered Danielle Mckinney’s work on the other side of the convergence of a global health emergency with my own private metamorphosis. If that had happened before, I would not have been able to stop and contemplate long enough to understand it—carried away as I was by the negotium of adult life.

“Adults, waiting for tomorrow, move in a present behind which is yesterday or the day before yesterday or at most last week: they don’t want to think about the rest. Children don’t know the meaning of yesterday, of the day before yesterday, or even of tomorrow, everything is this, now: the street is this, the doorway is this, the stairs are this, this is Mamma, this is Papa, this is the day, this the night.”6

1 Contrasting with the negative term negotium, which denoted public activity, business, and the quest for wealth and power, otium represented a time of respite from the demands of daily life. Whereas politicians and those who engage in public affairs serve a precise and practical purpose, philosophers have the entire human race as their audience, and their words are destined to endure over the centuries. Thus, according to Seneca, otium is a superior form of negotium.

2 Mckinney’s journey from photography to painting is a significant aspect of her artistic evolution. Initially trained as a photographer, Mckinney earned a BFA from the Atlanta College of Art and an MFA from Parsons School of Design. Her transition to painting, solidified during a two-year stay in Pont-Aven, France, allowed her to explore a medium that offered greater freedom and depth of expression. During the COVID-19 lockdown, Mckinney fully embraced painting, finding it a liberating space where she could engage with her subjects in a more intimate and contemplative manner.

3 “I can’t undo that photographic training—it’s embedded in how I begin a painting. First I paint the canvas with a black ground, and that black ground serves almost like the camera’s viewfinder. It allows me to build the image.” Taming the Bird: Danielle Mckinney, interview with Alison Gingeras, Mousse Magazine, May 2021. https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/danielle-mckinney-alison-gingeras-2021/. Last accessed July 18th, 2024.

4 Digital technology, along with the communication networks it supports, enables us to work around the clock, regardless of our location. In his influential book, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, visual culture theorist Jonathan Crary argues that these new media technologies have not ushered in an era of freedom and self-determination. Instead, they have entangled us in an even more pervasive web of control. Photography plays a crucial role in this dynamic, as it fuels the demand to constantly document and share our lives, enhancing our visibility and participation in a cycle of mutual self-surveillance.

5 Jia Tolentino, Ottessa Moshfegh’s Painful, Funny Novel of a Young Woman’s Chemical Hibernation, The New Yorker, July 11th, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/ottessa-moshfeghs-painful-funny-novel-of-a-young-womans-chemical-hibernation. Last accessed July 18th, 2024.

6 Elena Ferrante, My Brilliant Friend, Europa Editions, New York, 2012

The text was written on the occasion of the solo exhibition about a moment – in a moment by Danielle McKinney at Kunsthal n in Copenhagen, August 24, 2024 – January 5, 2025.

A catalogue was published in conjunction with the exhibition.