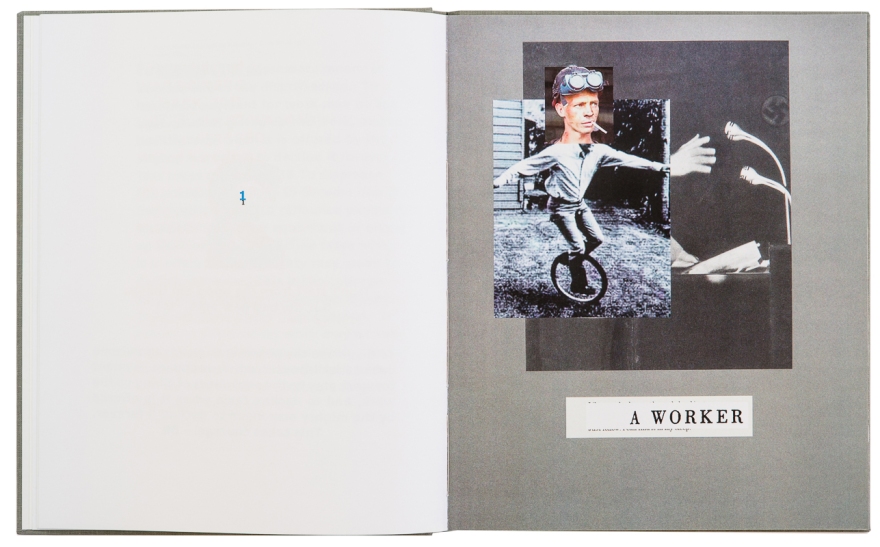

Ashes and Broken Brickwork of a Logical Theory (Roma Publications, 2010)

One Time One Million (Roma Publications, 2009)

RAY (Roma Publications, 2013)

Susanne Kriemann is a German artist whose work is characterised particularly by engagement with the medium of photography within a social-historical and archival context. By using countless photographic prints from different epochs, either made by the artist or collected by her, Kriemann takes on not only a historic and documentary aspect in her work, but at the same time indicates the associated meaning of the archive.

The reach of her investigative gaze includes the history of photography and kindred representations, Germany’s traumatic recent past, the obsolescence of industrialism and the constant metamorphosis of urban culture – all filtered through a relentless process of the medium’s self-questioning.

Paola Paleari: A clear critic towards positivism and modernism is embedded in your approach. At the same time, you make large use both of photography and of the archive, which are disciplines that were fostered by the same theories that are the aim of your critical discourse. Can you please explain the reasons of this focus in your practice?

Susanne Kriemann: I often focus on existing photographic archives and try to complicate the idea of an archive, since the archive for me is less one of containment than one of affect. For this reason, many of my projects narrate the particular affective relationship between a viewing community and a given archive. For example, my book Ashes and Broken Brickwork of a Logical Theory is visually framed by both Leonard Woolley’s Digging Up the Past (1930) and Agatha Christie’s They Came to Baghdad (1951). Christie was married to Mollowan and was his assistant on many archaeological expeditions, so she wrote and photographed there.

The reference to archaeology is very important in this work. The archaeological act is what forms an archive: it’s the pre-archival impulse. It’s a combination of the narrative of modernity/modernism questioned in Woolley’s work and the archival principles used to organise and distinguish artefacts in museums. The photographs in the book – which are taken by unknown photographers, Agatha Christie and myself – act as counterparts to the various uses/functions of photography as a tool to document, transcribe and quote.

PP: In One Time One Million, many perspectives are put together: history, ornithology, psychology, architecture and photography. Which role does the archive play when used in a multidiscipline approach? Is it exploited as a formal structure or for its conceptual implications?

SK: One Time One Million uses images coming from two distinct archives: birds photographed by Viktor Hasselblad himself and photographs of airplanes/ houses taken with Viktor Hasselblad’s first camera, the Ross HK 7.

I bought the Ross HK 7 camera together with two unexposed films at an auction in Stockholm in 2006. This “Hasselblad dinosaur” was the starting point of my research, and later became one of the protagonists of the work. In a similar way as the one I adopted in Ashes and Broken Brickwork of a Logical Theory, I chose a very specific approach to the archive, in order to find a few images that could represent the most precise points of reference for my concept.

Perhaps, to answer the second part of the question, it is important to remember that One Time One Million is both a book and an installation, and in the latter case I displayed the forty-six images as offset prints hung in a specially designed panopticum structure. This choice was motivated by the different sources of work files: 6×6 cm slides by Hasselblad, 7×9 cm b/w negatives by unknown pilots, my own aerial photographs shot with the 1948 b/w film, photographs in the ornithological collection of Berlin in 2009: I believe it would have destroyed the conceptual reading of the work, if I would have used all the technical implications of the images and printed each series accordingly. Therefore, when the book One Time One Million was printed, I decided to frame the first print run and it became a piece to be exhibited.

PP: RAY takes its premises from a radioactive rock discovered in Texas in the late XIX century. You often look for particular situations/collections/stories that you reinterpret and re-enact in your works. What importance do you give to curiosity? Is it more a tool to grasp the audience’s attention or a starting point for your creativity?

SK: This particular rock is part of a looping story, from the use of Gadolinium as a filament for Nernst street lamps that illuminate the AEG pavilion in the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, to the present use of this mineral in MRI scans. It’s also used in nuclear reactor control rods and smartphone touch screens. The rock was effectively part of the pictures, because I took them with my smartphone. I also made auto-radiographs by exposing films to the rock’s rays.

My goal was to transform the seeming durability of rocks into participating agents in our vertiginous stories and to show how rocks play a central role in our lives and in my work, moving them from background to foreground.

PP: Questioning the archive means facing concepts such as objet trouvé, détournement, de-contextualization, that that have been playing an important role in art since the Avant-garde movements of the ’20s. What has changed in the use of these solutions after postmodernism and the digital revolution? Why are we still making use of them?

I am not sure I can answer this question…

My own concern with photographs, which were taken, collected and archived by people of different times, is driven by an unquenchable appetite for new constellations of the interpretation of matter: however technology the images were produced with, this informs their political and social impact.

Working with scientific image collections, I am often confronted with terminologies such as geology and anthropology. These big concepts of how parts of the world were composed from a western, strongly male-gaze dominated activity, entangle with problems I am repulsed by and this often urges me to search and re-order them.

I believe that re-contextualizing specific images – or re-making images in precisely composed but substantially different conditions – is vital, at any time.

[Click here to go back to Punto de Fuga]